课程简介

- 所属大学:Harvard

- 先修要求:无

- 编程语言:C, Python, SQL, HTML, CSS, JavaScript

- 课程难度:🌟🌟

- 预计学时:20 小时

连续多年被哈佛大学学生评为最受欢迎的公选课程。Malan 教授上课非常有激情,撕黄页讲二分法的场面让人记忆犹新(笑)。但因为它的入门以及全校公选的属性,课程内容难度比较温和,但是课程作业质量非常高而且全部免费开源,非常适合小白入门,或者大佬休闲。

课程资源

资源汇总

@mancuoj 在学习这门课中用到的所有资源和作业实现都汇总在 mancuoj/CS50x - GitHub 中。

@figuretu 将有价值的提问讨论以及相关学习资源整理在共享文档 CS50 - 资源总目录 中。

Notes

C——Command-Line Arguments

Command-line argumentsare those arguments that are passed to your program at the command line. For example, all those statements you typed afterclangare considered command line arguments. You can use these arguments in your own programs!In your terminal window, type

code greet.cand write code as follows:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10// Uses get_string #include <cs50.h> #include <stdio.h> int main(void) { string answer = get_string("What's your name? "); printf("hello, %s\n", answer); }Notice that this says

helloto the user.Still, would it not be nice to be able to take arguments before the program even runs? Modify your code as follows:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16// Prints a command-line argument #include <cs50.h> #include <stdio.h> int main(int argc, string argv[]) { if (argc == 2) { printf("hello, %s\n", argv[1]); } else { printf("hello, world\n"); } }Notice that this program knows both

argc, the number of command line arguments, andargv, which is an array of the characters passed as arguments at the command line.Therefore, using the syntax of this program, executing

./greet Davidwould result in the program sayinghello, David.You can print each of the command-line arguments with the following:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12// Prints command-line arguments #include <cs50.h> #include <stdio.h> int main(int argc, string argv[]) { for (int i = 0; i < argc; i++) { printf("%s\n", argv[i]); } }

C——Exit Status

When a program ends, a special exit code is provided to the computer.

When a program exits without error, a status code of

0is provided to the computer. Often, when an error occurs that results in the program ending, a status of1is provided by the computer.You could write a program as follows that illustrates this by typing

code status.cand writing code as follows:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15// Returns explicit value from main #include <cs50.h> #include <stdio.h> int main(int argc, string argv[]) { if (argc != 2) { printf("Missing command-line argument\n"); return 1; } printf("hello, %s\n", argv[1]); return 0; }Notice that if you fail to provide

./status David, you will get an exit status of1. However, if you do provide./status David, you will get an exit status of0.You can type

echo $?in the terminal to see the exit status of the last run command.You can imagine how you might use portions of the above program to check if a user provided the correct number of command-line arguments.

Copying and malloc

A common need in programming is to copy one string to another.

In your terminal window, type

code copy.cand write code as follows:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22// Capitalizes a string #include <cs50.h> #include <ctype.h> #include <stdio.h> #include <string.h> int main(void) { // Get a string string s = get_string("s: "); // Copy string's address string t = s; // Capitalize first letter in string t[0] = toupper(t[0]); // Print string twice printf("s: %s\n", s); printf("t: %s\n", t); }Notice that

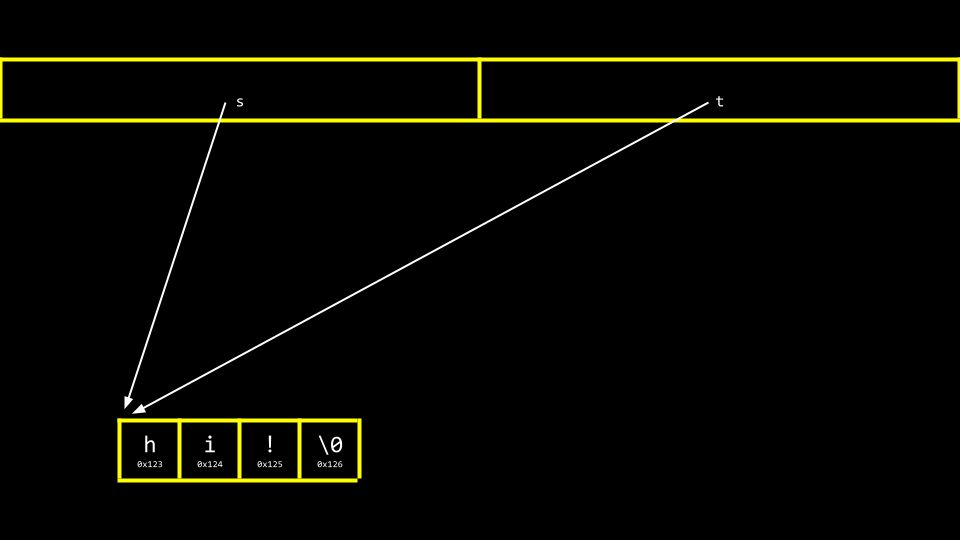

string t = scopies the address ofstot. This does not accomplish what we are desiring. The string is not copied – only the address is. Further, notice the inclusion ofctype.h.You can visualize the above code as follows:

Notice that

sandtare still pointing at the same blocks of memory. This is not an authentic copy of a string. Instead, these are two pointers pointing at the same string.Before we address this challenge, it’s important to ensure that we don’t experience a segmentation fault through our code, where we attempt to copy

string stostring t, wherestring tdoes not exist. We can employ thestrlenfunction as follows to assist with that:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25// Capitalizes a string, checking length first #include <cs50.h> #include <ctype.h> #include <stdio.h> #include <string.h> int main(void) { // Get a string string s = get_string("s: "); // Copy string's address string t = s; // Capitalize first letter in string if (strlen(t) > 0) { t[0] = toupper(t[0]); } // Print string twice printf("s: %s\n", s); printf("t: %s\n", t); }Notice that

strlenis used to make surestring texists. If it does not, nothing will be copied.To be able to make an authentic copy of the string, we will need to introduce two new building blocks. First,

mallocallows you, the programmer, to allocate a block of a specific size of memory. Second,freeallows you to tell the compiler to free up that block of memory you previously allocated.We can modify our code to create an authentic copy of our string as follows:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29// Capitalizes a copy of a string #include <cs50.h> #include <ctype.h> #include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> #include <string.h> int main(void) { // Get a string char *s = get_string("s: "); // Allocate memory for another string char *t = malloc(strlen(s) + 1); // Copy string into memory, including '\0' for (int i = 0; i <= strlen(s); i++) { t[i] = s[i]; } // Capitalize copy t[0] = toupper(t[0]); // Print strings printf("s: %s\n", s); printf("t: %s\n", t); }Notice that

malloc(strlen(s) + 1)creates a block of memory that is the length of the stringsplus one. This allows for the inclusion of the null\0character in our final copied string. Then, theforloop walks through the stringsand assigns each value to that same location on the stringt.It turns out that our code is inefficient. Modify your code as follows:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29// Capitalizes a copy of a string, defining n in loop too #include <cs50.h> #include <ctype.h> #include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> #include <string.h> int main(void) { // Get a string char *s = get_string("s: "); // Allocate memory for another string char *t = malloc(strlen(s) + 1); // Copy string into memory, including '\0' for (int i = 0, n = strlen(s); i <= n; i++) { t[i] = s[i]; } // Capitalize copy t[0] = toupper(t[0]); // Print strings printf("s: %s\n", s); printf("t: %s\n", t); }Notice that

n = strlen(s)is defined now in the left-hand side of thefor loop. It’s best not to call unneeded functions in the middle condition of theforloop, as it will run over and over again. When movingn = strlen(s)to the left-hand side, the functionstrlenonly runs once.The

CLanguage has a built-in function to copy strings calledstrcpy. It can be implemented as follows:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26// Capitalizes a copy of a string using strcpy #include <cs50.h> #include <ctype.h> #include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> #include <string.h> int main(void) { // Get a string char *s = get_string("s: "); // Allocate memory for another string char *t = malloc(strlen(s) + 1); // Copy string into memory strcpy(t, s); // Capitalize copy t[0] = toupper(t[0]); // Print strings printf("s: %s\n", s); printf("t: %s\n", t); }Notice that

strcpydoes the same work that ourforloop previously did.Both

get_stringandmallocreturnNULL, a special value in memory, in the event that something goes wrong. You can write code that can check for thisNULLcondition as follows:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41// Capitalizes a copy of a string without memory errors #include <cs50.h> #include <ctype.h> #include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> #include <string.h> int main(void) { // Get a string char *s = get_string("s: "); if (s == NULL) { return 1; } // Allocate memory for another string char *t = malloc(strlen(s) + 1); if (t == NULL) { return 1; } // Copy string into memory strcpy(t, s); // Capitalize copy if (strlen(t) > 0) { t[0] = toupper(t[0]); } // Print strings printf("s: %s\n", s); printf("t: %s\n", t); // Free memory free(t); return 0; }Notice that if the string obtained is of length

0or malloc fails,NULLis returned. Further, notice thatfreelets the computer know you are done with this block of memory you created viamalloc.

Valgrind

Valgrind is a tool that can check to see if there are memory-related issues with your programs wherein you utilized

malloc. Specifically, it checks to see if youfreeall the memory you allocated.Consider the following code for

memory.c:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12// Demonstrates memory errors via valgrind #include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> int main(void) { int *x = malloc(3 * sizeof(int)); x[1] = 72; x[2] = 73; x[3] = 33; }Notice that running this program does not cause any errors. While

mallocis used to allocate enough memory for an array, the code fails tofreethat allocated memory.If you type

make memoryfollowed byvalgrind ./memory, you will get a report from valgrind that will report where memory has been lost as a result of your program. One error that valgrind reveals is that we attempted to assign the value of33at the 4th position of the array, where we only allocated an array of size3. Another error is that we never freedx.You can modify your code to free the memory of

xas follows:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13// Demonstrates memory errors via valgrind #include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> int main(void) { int *x = malloc(3 * sizeof(int)); x[1] = 72; x[2] = 73; x[3] = 33; free(x); }Notice that running valgrind again now results in no memory leaks.

Garbage Values

When you ask the compiler for a block of memory, there is no guarantee that this memory will be empty.

It’s very possible that the memory you allocated was previously utilized by the computer. Accordingly, you may see junk or garbage values. This is a result of you getting a block of memory but not initializing it. For example, consider the following code for

garbage.c:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11#include <stdio.h> #include <stdlib.h> int main(void) { int scores[1024]; for (int i = 0; i < 1024; i++) { printf("%i\n", scores[i]); } }Notice that running this code will allocate

1024locations in memory for your array, but theforloop will likely show that not all values therein are0. It’s always best practice to be aware of the potential for garbage values when you do not initialize blocks of memory to some other value like zero or otherwise.

Tries

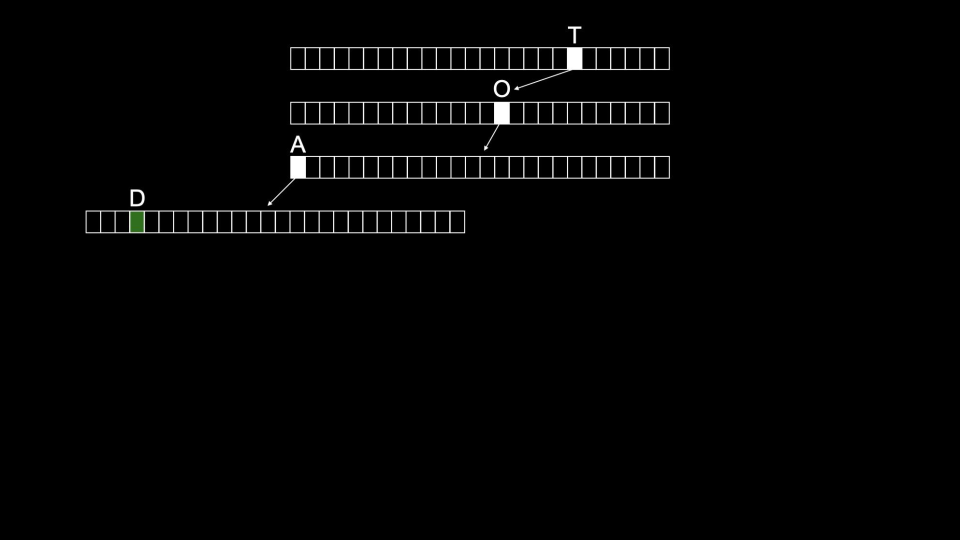

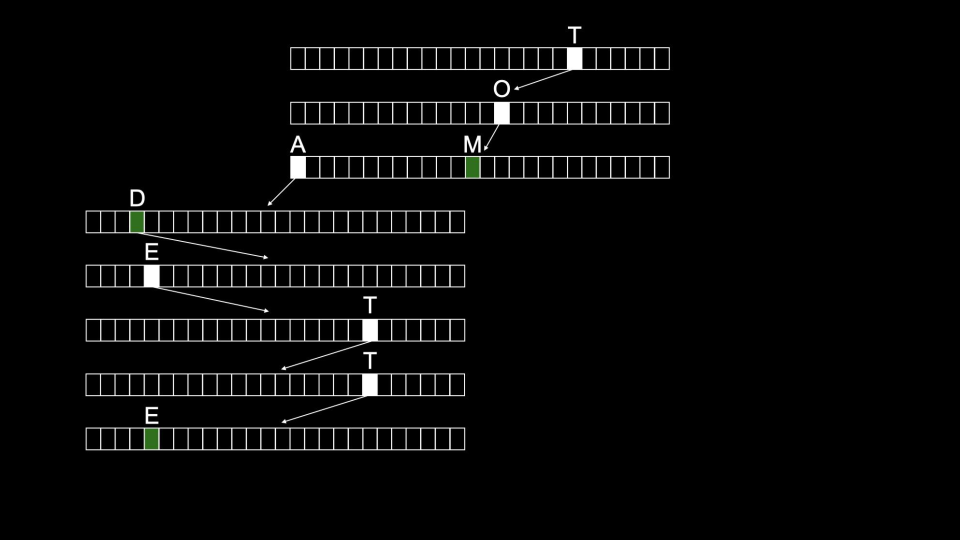

Tries are another form of data structure. Tries are trees of arrays.

Tries are always searchable in constant time.

One downside to Tries is that they tend to take up a large amount of memory. Notice that we need 26 ×4 =104

nodes just to store Toad!Toad would be stored as follows:

Tom would then be stored as follows:

This structure offers a search time of 𝑂(1).

The downside of this structure is how many resources are required to use it.

Python——Command-Line Arguments

As with C, you can also utilize command-line arguments. Consider the following code:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8# Prints a command-line argument from sys import argv if len(argv) == 2: print(f"hello, {argv[1]}") else: print("hello, world")Notice that

argv[1]is printed using a formatted string, noted by thefpresent in theprintstatement.You can learn more about the

syslibrary in the Python documentation

Python——Exit Status

The

syslibrary also has built-in methods. We can usesys.exit(i)to exit the program with a specific exit code:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10# Exits with explicit value, importing sys import sys if len(sys.argv) != 2: print("Missing command-line argument") sys.exit(1) print(f"hello, {sys.argv[1]}") sys.exit(0)Notice that dot-notation is used to utilize the built-in functions of

sys.

Relational Databases

Google, X, and Meta all use relational databases to store their information at scale.

Relational databases store data in rows and columns in structures called tables.

SQL allows for four types of commands:

1 2 3 4Create Read Update DeleteThese four operations are affectionately called CRUD.

We can create a database with the SQL syntax

CREATE TABLE table (column type, ...);. But where do you run this command?sqlite3is a type of SQL database that has the core features required for this course.We can create a SQL database at the terminal by typing

sqlite3 favorites.db. Upon being prompted, we will agree that we want to createfavorites.dbby pressingy.You will notice a different prompt as we are now using a program called

sqlite.We can put

sqliteintocsvmode by typing.mode csv. Then, we can import our data from ourcsvfile by typing.import favorites.csv favorites. It seems that nothing has happened!We can type

.schemato see the structure of the database.You can read items from a table using the syntax

SELECT columns FROM table.For example, you can type

SELECT * FROM favorites;which will print every row infavorites.You can get a subset of the data using the command

SELECT language FROM favorites;.SQL supports many commands to access data, including:

1 2 3 4 5 6 7AVG COUNT DISTINCT LOWER MAX MIN UPPERFor example, you can type

SELECT COUNT(*) FROM favorites;. Further, you can typeSELECT DISTINCT language FROM favorites;to get a list of the individual languages within the database. You could even typeSELECT COUNT(DISTINCT language) FROM favorites;to get a count of those.SQL offers additional commands we can utilize in our queries:

1 2 3 4 5WHERE -- adding a Boolean expression to filter our data LIKE -- filtering responses more loosely ORDER BY -- ordering responses LIMIT -- limiting the number of responses GROUP BY -- grouping responses togetherNotice that we use

--to write a comment in SQL.

SQL Injection Attacks

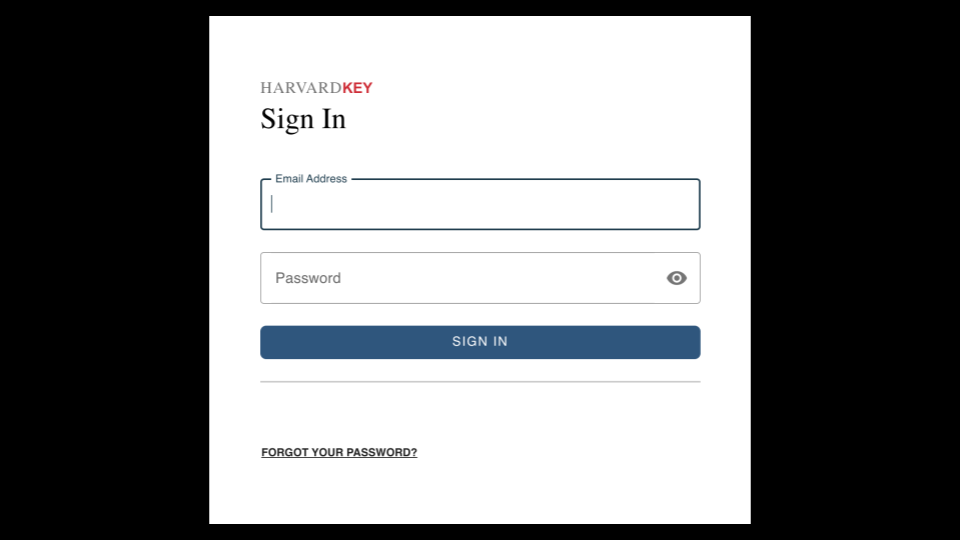

Now, still considering the code above, you might be wondering what the

?question marks do above. One of the problems that can arise in real-world applications of SQL is what is called an injection attack. An injection attack is where a malicious actor could input malicious SQL code.For example, consider a login screen as follows:

Without the proper protections in our own code, a bad actor could run malicious code. Consider the following:

1rows = db.execute("SELECT COUNT(*) FROM users WHERE username = ? AND password = ?", username, password)Notice that because the

?is in place, validation can be run onfavoritebefore it is blindly accepted by the query.You never want to utilize formatted strings in queries as above or blindly trust the user’s input.

Utilizing the CS50 Library, the library will sanitize and remove any potentially malicious characters.

http-server

Up until this point, all HTML you saw was pre-written and static.

In the past, when you visited a page, the browser downloaded an HTML page, and you were able to view it. These are considered static pages, in that what is programmed in the HTML is exactly what the user sees and downloads client-side to their internet browser.

Dynamic pages refer to the ability of Python and similar languages to create HTML on-the-fly. Accordingly, you can have web pages that are generated server-side by code based upon the input or behavior of users.

You have used

http-serverin the past to serve your web pages. Today, we are going to utilize a new server that can parse out a web address and perform actions based on the URL provided.Further, last week, you saw URLs as follows:

1https://www.example.com/folder/file.htmlNotice that

file.htmlis an HTML file inside a folder calledfolderatexample.com.

Cookies and Session

app.pyis considered a controller. A view is considered what the users see. A model is how data is stored and manipulated. Together, this is referred to as MVC (model, view, controller).While the prior implementation of

froshimsis useful from an administrative standpoint, where a back-office administrator could add and remove individuals from the database, one can imagine how this code is not safe to implement on a public server.For one, bad actors could make decisions on behalf of other users by hitting the deregister button – effectively deleting their recorded answer from the server.

Web services like Google use login credentials to ensure users only have access to the right data.

We can actually implement this itself using cookies. Cookies are small files that are stored on your computer such that your computer can communicate with the server and effectively say, “I’m an authorized user that has already logged in.” This authorization through this cookie is called a session.

Cookies may be stored as follows:

1 2 3GET / HTTP/2 Host: accounts.google.com Cookie: session=valueHere, a

sessionid is stored with a particularvaluerepresenting that session.In the simplest form, we can implement this by creating a folder called

loginand then adding the following files.First, create a file called

requirements.txtthat reads as follows:1 2Flask Flask-SessionNotice that in addition to

Flask, we also includeFlask-Session, which is required to support login sessions.Second, in a

templatesfolder, create a file calledlayout.htmlthat appears as follows:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14<!DOCTYPE html> <html lang="en"> <head> <meta name="viewport" content="initial-scale=1, width=device-width"> <title>login</title> </head> <body> {% block body %}{% endblock %} </body> </html>Notice this provides a very simple layout with a title and a body.

Third, create a file in the

templatesfolder calledindex.htmlthat appears as follows:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11{% extends "layout.html" %} {% block body %} {% if name -%} You are logged in as {{ name }}. <a href="/logout">Log out</a>. {%- else -%} You are not logged in. <a href="/login">Log in</a>. {%- endif %} {% endblock %}Notice that this file looks to see if

session["name"]exists (elaborated further inapp.pybelow). If it does, it will display a welcome message. If not, it will recommend you browse to a page to log in.Fourth, create a file called

login.htmland add the following code:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10{% extends "layout.html" %} {% block body %} <form action="/login" method="post"> <input autocomplete="off" autofocus name="name" placeholder="Name" type="text"> <button type="submit">Log In</button> </form> {% endblock %}Notice this is the layout of a basic login page.

Finally, create a file called

app.pyand write code as follows:1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29from flask import Flask, redirect, render_template, request, session from flask_session import Session # Configure app app = Flask(__name__) # Configure session app.config["SESSION_PERMANENT"] = False app.config["SESSION_TYPE"] = "filesystem" Session(app) @app.route("/") def index(): return render_template("index.html", name=session.get("name")) @app.route("/login", methods=["GET", "POST"]) def login(): if request.method == "POST": session["name"] = request.form.get("name") return redirect("/") return render_template("login.html") @app.route("/logout") def logout(): session.clear() return redirect("/")Notice the modified imports at the top of the file, including

session, which will allow you to support sessions. Most importantly, notice howsession["name"]is used in theloginandlogoutroutes. Theloginroute will assign the login name provided and assign it tosession["name"]. However, in thelogoutroute, the logging out is implemented by clearing the value ofsession.The

sessionabstraction allows you to ensure only a specific user has access to specific data and features in our application. It allows you to ensure that no one acts on behalf of another user, for good or bad!If you wish, you can download our implementation of

login.You can read more about sessions in the Flask documentation.